By the end of the decade, agencies once considered secure were also changing hands. In 1987, Martin Sorrell’s WPP Group acquired J. Walter Thompson Co. for $566 million. Although it was not a hostile takeover, the partners of Lord, Geller, Federico, Einstein, itself a JWTacquisition, quit in protest, resulting in a court battle that cost them $7 million.

Two years later, WPP acquired Ogilvy Group which included Ogilvy & Matherin a bitter hostile takeover, the first in advertising history, in which agency founder David Ogilvy publicly attacked Mr. Sorrell.

Saatchi & Saatchi, which had acquired McCaffrey & McCall earlier in the decade, absorbed Dancer-Fitzgerald-Sample, Backer & Spielvogel and Ted Bates & Co. in a deal that also included Bates subsidiaries Campbell-Mithun and William Esty Co.

In 1986, Omnicom was created, merging Needham, Harper & Steers Advertising and Doyle Dane Bernbach into DDB Needham and maintaining Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn, the third agency in the deal, under its own name.

Agency consolidations were driven by three factors: Banks and other lending institutions were willing to finance highly leveraged acquisitions; agencies that were bringing in huge profits had money to spend on acquisitions; and agencies were looking for ways to increase profitability.

Of the top 15 U.S. agencies at the start of the decade, only Leo Burnett Co., Young & Rubicam, McCann-Erickson and Grey Advertising survived the 1980s with their ownership intact. With a recession that developed late in the decade, however, the agency “buying binge” slowed.

The “decade of the deal,” as Advertising Age called it, also affected advertisers: Of the 100 largest advertisers in 1980, only a third were still independent by 1990.

Financier Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. scored the greatest leveraged buyout of the decade with its purchase of Nabisco for $25 billion, a deal that also included Standard Brands, which Nabisco had already absorbed. Philip Morris Cos. bought Kraft, Kodak bought Sterling Drug and Grand Metropolitan of England bought Pillsbury. Companies such as Kroger Foods fought against takeovers but found the battle expensive, and much of the cost was reflected in diminished ad spending.

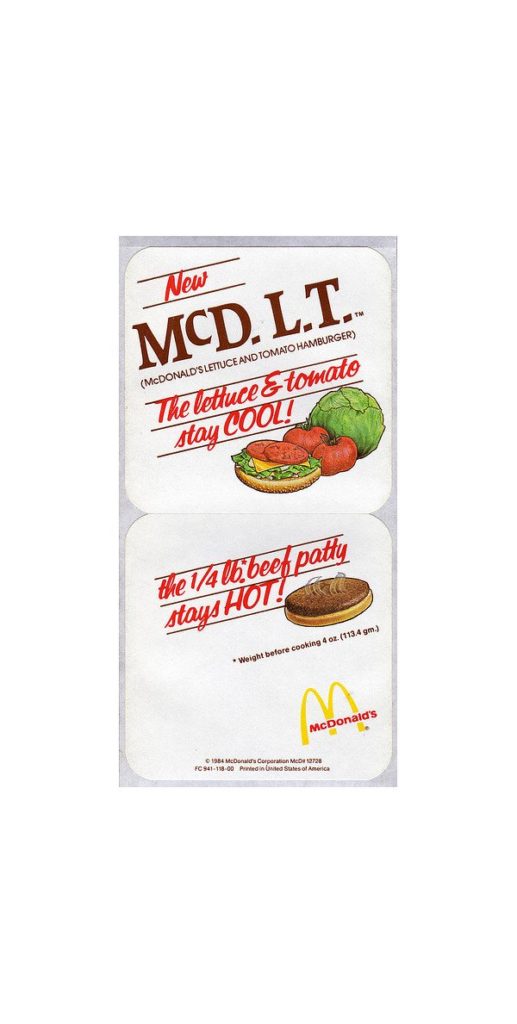

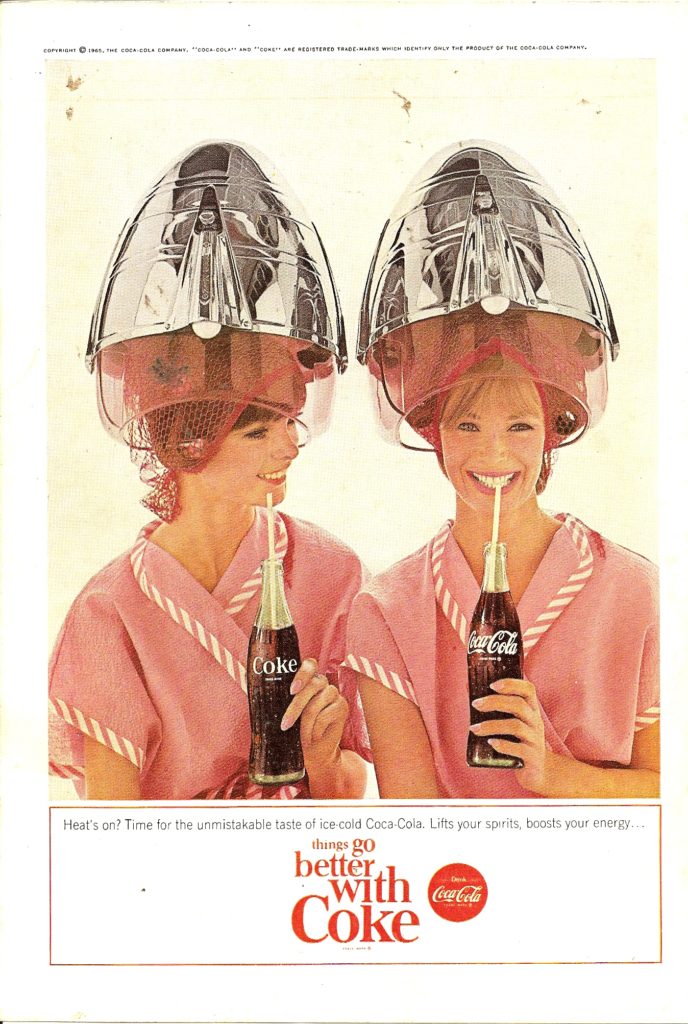

Several companies that had long been international marketers?such as Coca-Cola Co., IBM Corp., General Motors Corp., Monsanto and McDonald’s Corp.?were joined by countless others seeking their share of the world market as they made international advertising part of their general advertising strategy.

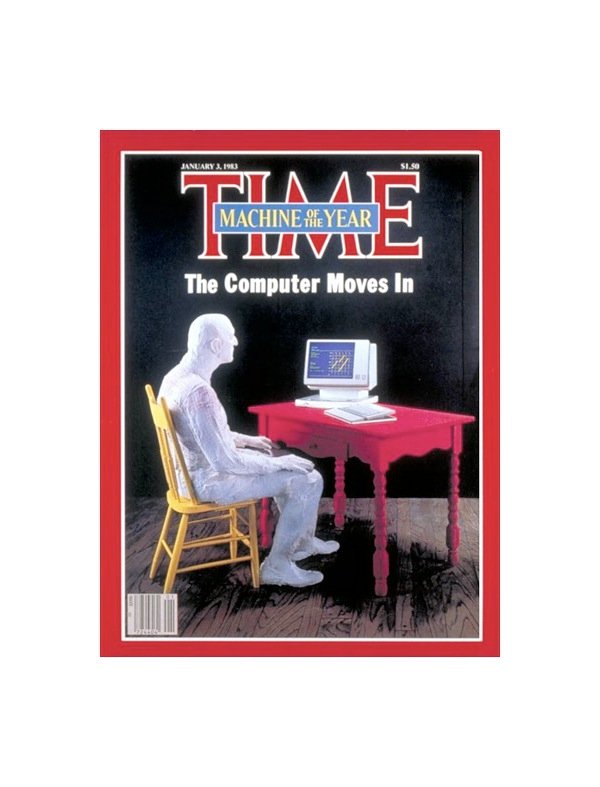

Effects of technology

Cable TV had a profound impact in reshaping the TV industry during the decade. As cable channels prospered, they undermined the influence of traditional broadcast networks. By the early 1990s, the once-dominant broadcast networks saw their portion of the evening TV audience slip to less than 60%. Whereas ABC, NBC and CBS each claimed about 19% of the TV audience, “independent” TV and cable TV, as exemplified by CNN (launched in 1980) and MTV (1982), captured more than 40%.

In addition to cable TV, the VCR allowed viewers to manage, organize and control the programs available to them. In addition, remote controls gave TV viewers the ability to “zip” and “zap” their way through TV commercials. The term “zipping” was coined to describe the practice of using the remote control to change channels during commercials. Viewers could also “zap” commercials out of recorded programs by fast-forwarding through them, thus ignoring ad messages. Eventually, certain VCRs were marketed that could be programmed to automatically skip commercials, compounding the problem for advertisers.

Cable TV further contributed to the internationalization of advertising. CNN sold advertising worldwide, offering companies the ability to advertise their products to a worldwide audience.

A new form of electronic advertising, direct-response home shopping services, developed in the ’80s. Cable networks such as the Home Shopping Network (launched in 1982) and QVC (1986) sold discounted goods directly to viewers, who called in orders to telephone operators. Instead of purchasing airtime for advertising from cable operators, home-shopping networks paid cable operators a percentage of the profits from sales generated in their viewing area.

The infomercial, another new ad vehicle, became one of the fastest-growing areas in TV advertising. These 30-minute commercials often featured celebrities and appeared as news or informational programming; in reality, they were promotional pitches for all types of products.

In an effort to maximize profits and enhance ad effectiveness, agencies made a shift in the mid-1980s to 15-second TV spots, moving away from the earlier 30-second standard. The new :15s theoretically allowed advertisers to double the number of ads run and reduce the cost per ad, maintaining and often increasing revenue levels. The shorter spots posed a new creative challenge to the industry, which had to pack incentive to purchase and product information into a shorter message. They also drew critics, who claimed they were cluttering the airwaves.

Noteworthy advertising

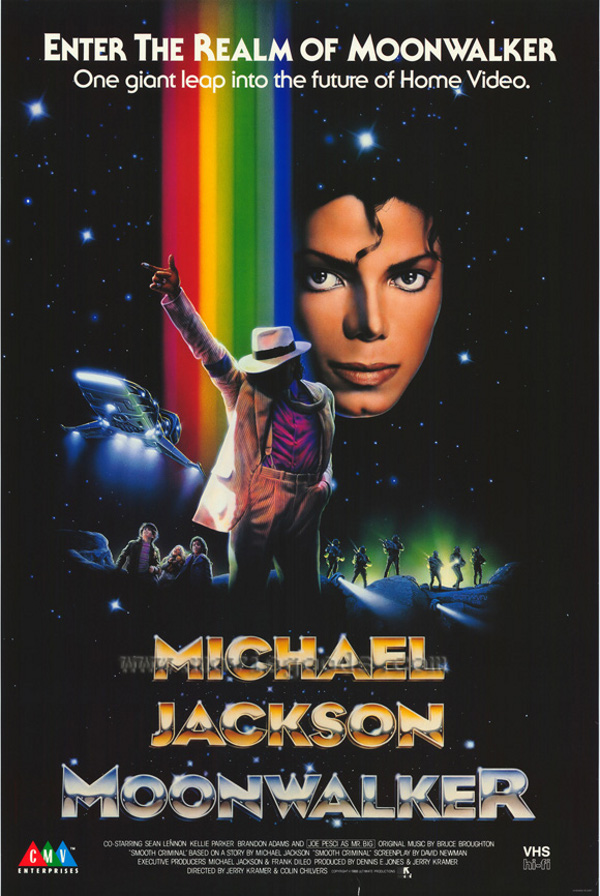

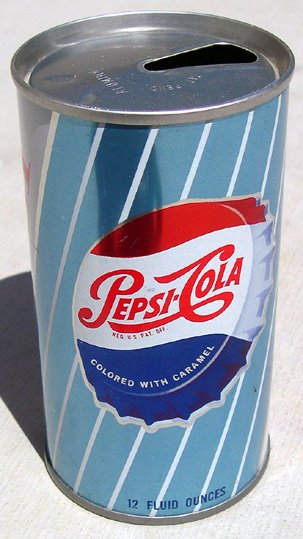

Pepsi-Cola changed its slogan in the 1980s from “Pepsi generation” to “Choice of a new generation” with the help of BBDO and contracted with music icon Michael Jackson in one of the largest celebrity endorsement agreements in advertising history.

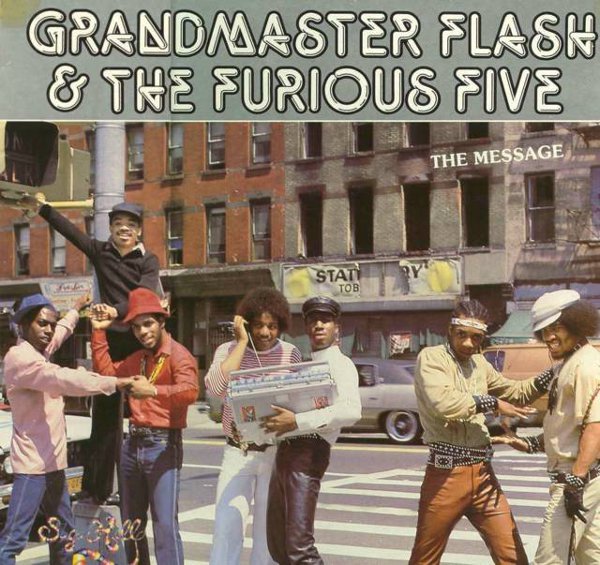

“Lunch Box,” for the California Raisins Advisory Board, featured hip Claymation raisins wearing sunglasses and shuffling to the 1960s hit tune “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” Foote, Cone & Belding, San Francisco, was the agency behind the 1986 spot.

Memorable as well was the Cheer commercial in which a silent, deadpan presenter smudged a handkerchief and put it in a cocktail shaker with water, ice and a dash of the detergent. With an opera aria as background music, viewers saw that the hankie, of course, was spotless when pulled from the shaker.

The Energizer Bunny, ranked among the top icons in advertising history by Advertising Age, was introduced in 1989. The commercials, from Chiat/Day, were called the “ultimate product demo” because they showed the product’s unique selling proposition?long-lived batteries?in an inventive, fresh way. The Bunny first appeared in three :15s, sending up coffee, wine and decongestant spots.

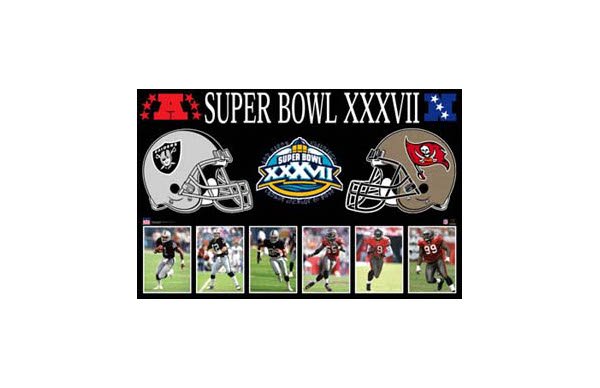

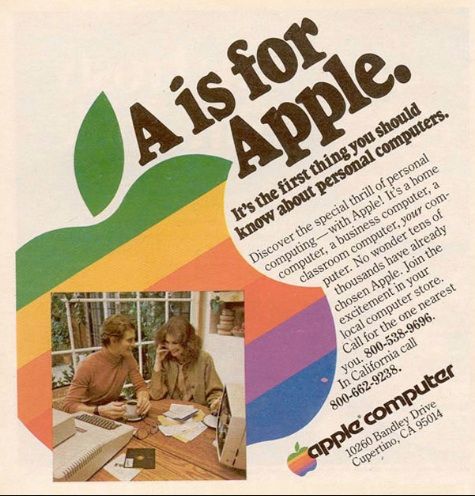

Perhaps one of the best commercials?and marketing strategies?of all time was the Orwellian Apple Macintosh advertisement entitled “1984,” which launched the Macintosh revolution. The one-time airing of the 60-second spot during the 1984 Super Bowl became a watershed of American advertising.

That same year, a senior citizen named Clara Peller became a star when she appeared in a now-classic Wendy’s commercial (“Where’s the Beef?”), produced by Dancer-Fitzgerald-Sample and directed by Joe Sedelmaier.

In 1986, JWT introduced “Herb,” a man who had never tried a Whopper, for Burger King. Viewers were urged to be on the lookout for Herb in Burger King outlets, but the campaign was dropped four months later. Advertising Age later termed it “the most elaborate advertising flop of the decade.”

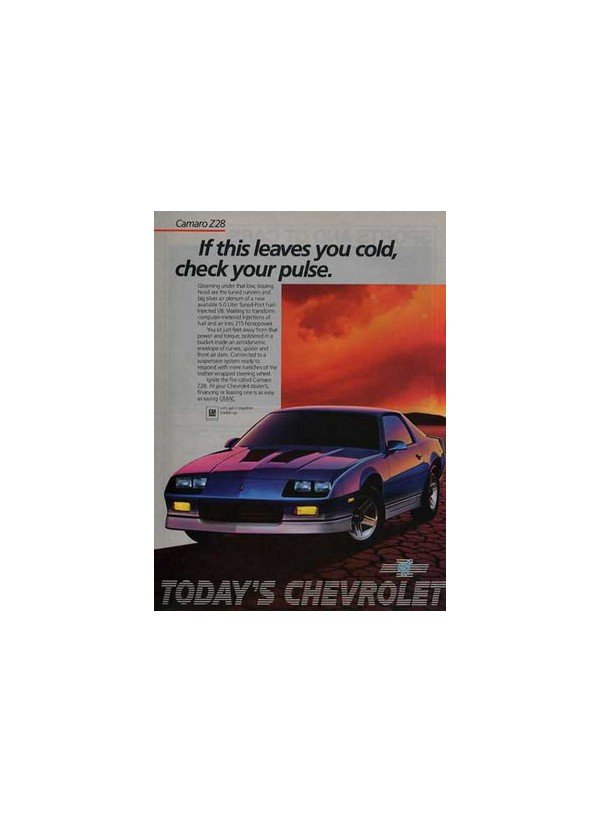

In reaction to the inroads that foreign automakers were making in the U.S. market, U.S. advertisers responded with increasing defensiveness. Ads told the American people, “At Ford quality is job one” and “GM puts quality on the road.”

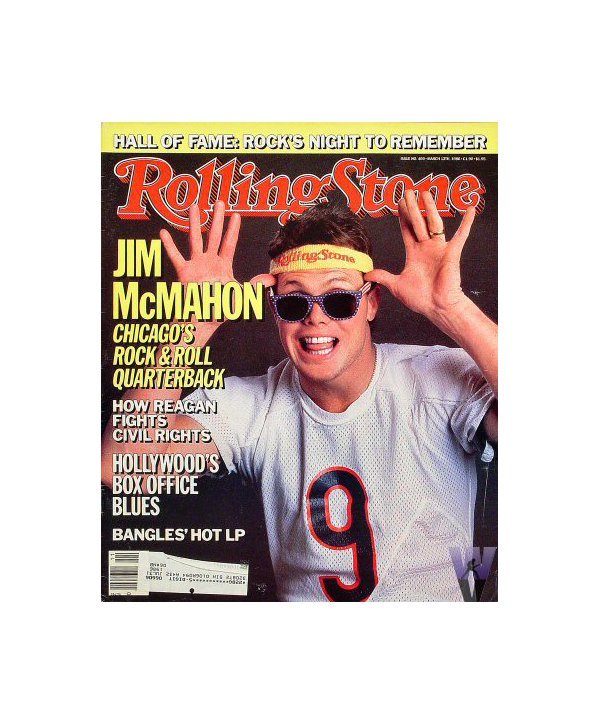

Other noteworthy campaigns from the ’80s included E&J Gallo Winery’s “plain folks” approach from Hal Riney & Partners for Bartles & Jaymes wine cooler; Lee Iacocca’s debut in Kenyon & Eckhardt-produced spots for Chrysler; Ally & Gargano’s “fast-talker” spots for Federal Express; Coca-Cola’s “Mean Joe Greene” spot from McCann-Erickson; Della Femina, Travisano & Partners’ exaggerating Joe Isuzu character for automaker Isuzu; and Calvin Klein’s spots tagged, “Know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing,” featuring teen-age spokesmodel Brooke Shields. At the end of the decade, Nissan grabbed attention with its “rocks & trees” campaign from Hill, Holliday, Connors, Cosmopulos for its luxury Infinity, which never showed the car.

Politics, critics, milestones

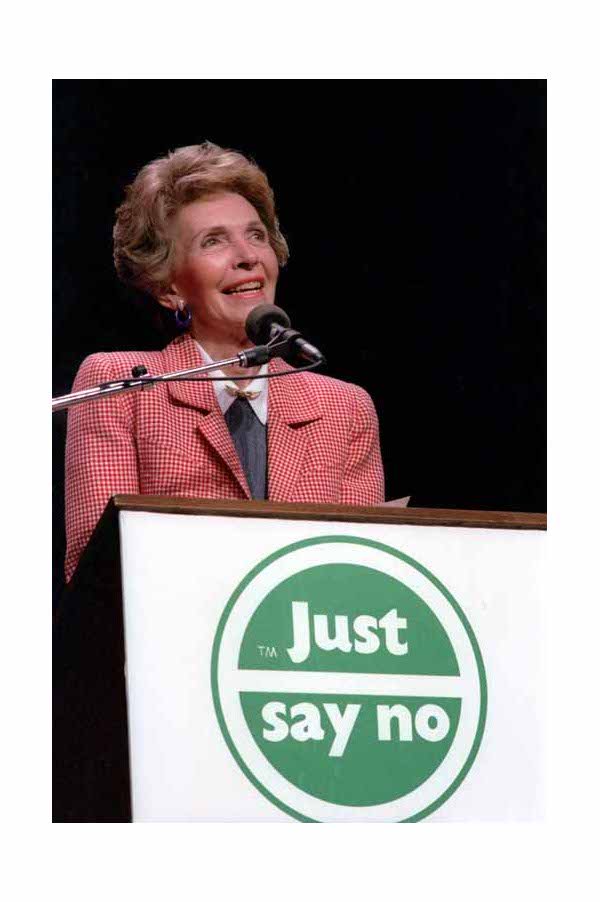

No discussion of advertising in the 1980s would be complete without noting the high priority placed on TV advertising by the re-election campaign of President Ronald Reagan. The Reagan “feel good” spot for the 1984 campaign, handled by the re-election team’s ad hoc Tuesday Team and written by Hal Riney, included a number of patriotic vignettes on the theme “It’s morning again in America.”

In his handling of the 1984 campaign, President Reagan dramatically altered the traditional relationship between the media and politics. He and his aides staged news events for maximum media coverage, timed announcements to be seen by large TV audiences and demonstrated an unprecedented understanding of the power of visual media.

The 1980s were marked by some serious criticism and challenges for the advertising industry. For example, long-held assumptions about advertising’s effectiveness were challenged by Gerald Tellis, who put together a sophisticated statistical model and concluded that people are relatively unmoved by TV advertisements in making brand choices, especially with regard to everyday products. His 1983-84 examination of consumer purchasing patterns generated discussion and concern. The research continued into the 1990s.

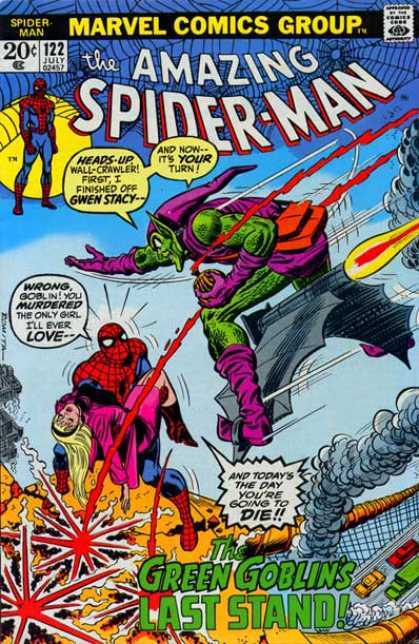

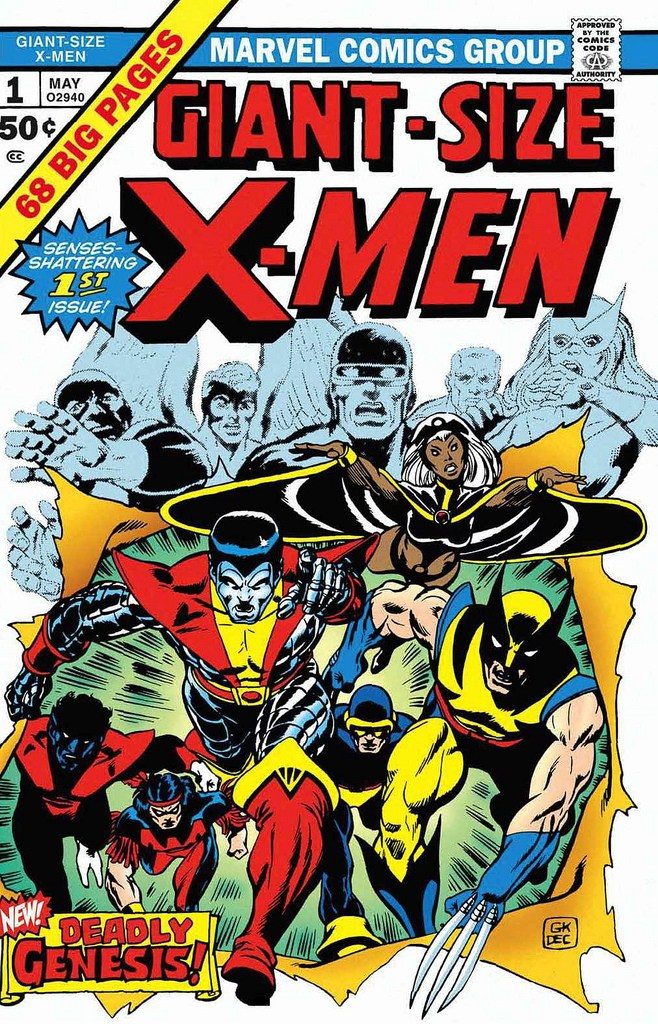

Government deregulation under President Reagan ushered in a philosophy of “less government” and more free marketplace decision-making and autonomy. During the Reagan presidency, a political and economic environment was created that allowed for mergers and acquisitions and also tolerated tremendous corporate media growth. In 1986, General Electric Corp. was allowed to purchase RCA Corp., which already owned NBC. In 1989, Time bought Warner Communications and formed Time-Warner, bringing together under a single corporate umbrella an empire consisting of magazines, motion picture and TV production companies, cable TV networks, book publishers, record companies and a major comic books company.

Other significant milestones of the 1980s include the introduction of Rely tampons by Procter & Gamble Co. in May 1980 and the subsequent withdrawal of the product four months later when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control linked its use to toxic shock syndrome. Two years later Tylenol capsules were pulled from shelves across the U.S. after an incidence of product tampering in Chicago that resulted in seven deaths.

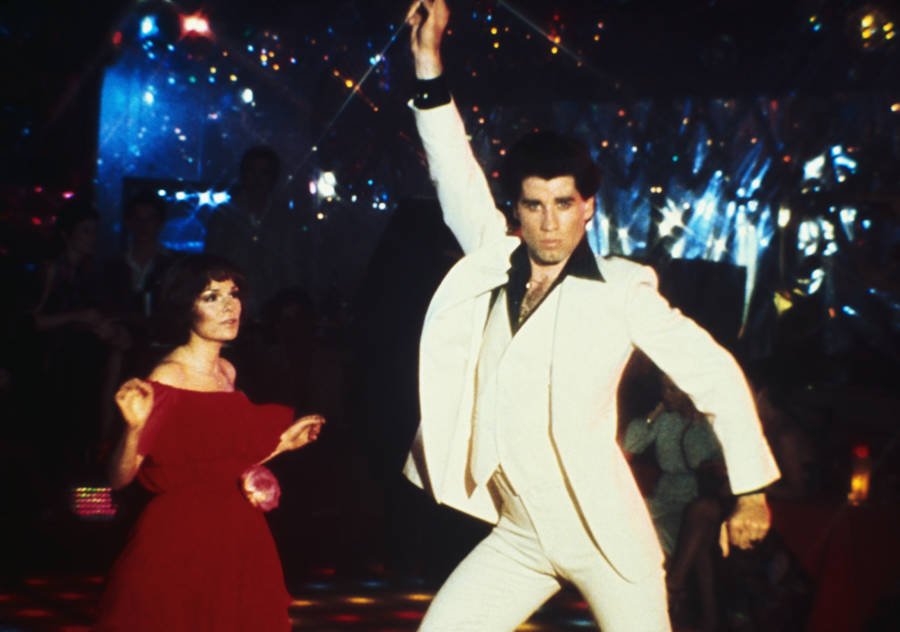

In addition, the decade saw the sudden rise of blue jeans into the realm of high fashion with such brands as Sergio Valente, Bon Jour, Calvin Klein, Gloria Vanderbilt and Jordache. Hershey’s Reese’s Pieces saw sales leap 70% in 1982 after its exposure via product placement in the movie “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.”

Caffeine-free soft drinks were introduced in 1983, and AT&T Corp. divested itself of its local phone companies, which became seven independent regional companies known collectively as the “Baby Bells.” ACNielsen Corp. was sold to Dun & Bradstreet Corp. in 1984, and Nike signed Chicago Bulls rookie Michael Jordan in a deal said to cover five years for $2.5 million. The following year, Capital Cities Communications acquired ABC for $3.5 billion. In response to the spread of AIDS, which by mid-decade had become an epidemic, magazines such as Bride’s, Family Circle, Parents and Vogue began accepting ads for condoms in 1986.

In 1986, “The Cosby Show” commanded a record $400,000 for a 30-second spot. Oat bran became a sensation in 1989 when research suggested it might help reduce cholesterol. Kellogg, General Mills, Quaker, Nabisco, Post and even Mrs. Field’s competed for their share of the oat bran market.

![]()